Fish and the sea remain deeply mysterious to me. It would seem that fish has always been regarded as something quite different from meat, from the ancient Greeks – who kept their land animals for the gods – to the Catholic church, which, most notably in medieval times, set aside a great many days for fasting and fish-eating. The implication there is that all eating is more or less sinful, on a sliding scale down from red meat; we might remember that the eating of animals was a sop to the debased postdiluvian world, as Jahweh realised that his creations would never quite be able to control themselves. Anyone who has worked in a restaurant will have noticed that a lot of people, devoutly or not, still eat fish on Fridays (the chippy is usually heaving then too) – abstention has become a treat. This is not, I think, how the ban would have been experienced originally, at least by the rich, monks and the priesthood included, whose meals consisted not of a main protein and trimmings but of a number of different dishes and delicacies, fish, fowl, fresh and salt meat, cakes, pastries and so on; the injunction to eat fish would, rather than involving a straight swap between creatures, have meant the loss of a great deal of variety at table – though I doubt anyone (I’m still talking about rich people) went hungry because of it. At any rate, although fish may now be eaten as a pleasurable rarity rather than under duress, the distinction between it on the one hand, and birds and mammals on the other, is still maintained. Personally, I almost never cook fish at home. The difficulty first in sourcing it (fishmonger’s can be wretched places, reeking and dripping – when you find a good one, hold on to it) and then in cooking it, which seems to need pans of an impeccable non-stickness, or fish kettles and racks of a different size and shape for every species, always appears insurmountable.

It isn’t, of course, as I rediscover every time I actually do it. Most fish cooking is actually very easy, an excellent vehicle for bold simplicity. As I think Hugh FW points out on a few occasions, all you have to do to cook fish, with a few exceptions, is get it hot. None of the angst of rare beef, medium-rare lamb, slow-cooked, melting pork – just get it hot, but not too hot. To cook a fillet of bass or bream to crisp-skinned, melting perfection, just oil and salt a cold frying pan, and put the fish, skin-side down, into it. Place over a low-medium heat, and leave there. If you’re worried about the skin sticking, use a lot of oil. By the time the flesh is cooked – opaque, flaking – the skin should be a lovely golden brown. If you’re bothered about such things, then you can fry it on the other side for a minute to sear the flesh. Spoon some butter around it at this point, perhaps some herbs and black pepper, and the fish is done. Poaching fish is even easier, but seems to have fallen out of fashion somewhat.

Despite all this, you might still prefer to eat your fish out of doors. Fair enough. Fish, as is well known, tastes significantly better by the sea, the spray of which provides an elementary seasoning to the tongue, as well as a not-entirely-reliable guarantee of freshness, and in the dying stages of extreme sunlight, accompanied by a glass of something very cold and quite possibly fizzy – Bass shandy, at a pinch. Experts differ as to whether the best seasides for fish-eating are found in North Norfolk, pebble-strewn Kent, urban Barcelona or Palermo, the cruel beaches of Yorkshire or the softer ones of the Suffolk heritage coast, the Greek Islands, the rocks of the Hebrides, the drunken evenings of adulthood or the gentler exhaustion of childhood; this is surely just a matter of taste, though, and any opinion is necessarily partisan. Everyone agrees, however, that while white fish is best by the seaside, the flavours of oily fish and shellfish travel a little better – though since their flesh does not, they must generally be preserved in some form or another for their journey.

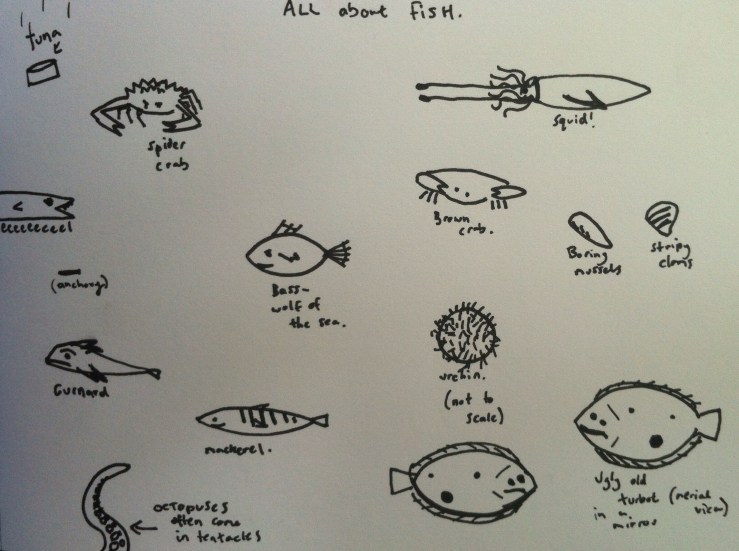

Time was that every fishing town would have had their specialities, and many still survive in odd little cafes or the right kind of gastropub – roll-mops (although the Italians are the undisputed champions of food-related insults, ‘roll-mop’ as a term of abuse for someone with ‘no guts and no spine’ is a particularly excellent British one), kippers, bloaters, smoked and jellied eels, hot- or cold-smoked salmon, mackerel, herring, pickled winkles, cockles, and mussels in little pots or bags; although we still tend to keep these molluscs for seaside treats, you see them in jars at the supermarket, and I presume people eat them. Although heavily smoked fish makes a pungent addition to the breakfast table, the only sea-creature to really cross over into the day-to-day meat-eating world is the tiny anchovy. I don’t think I’ve ever seen a fresh one, which are to be found in great heaps in Mediterranean fish-markets, in this country, and although the soused ones the Spanish call boquerones are making inroads here, it is the salted fillets – brown, rottingly pungent, barely recognisable as fish – that found a real place in British cooking. The Romans left fish guts to ferment in the sun, bottled up the remains and called it garum; South East Asia has its intensely savoury fish and shellfish sauces; we have Worcester sauce, a deeply odd concoction containing, among other, secret things, anchovies. There are few things that are really, genuinely better to eat than Cheddar cheese, melted onto thick white toast, with a few splashes of Worcester sauce on top; add some pickled onions and you have a complete if smelly meal. Although you might, as you grow older, come to prefer a few anchovies spiked, alongside garlic and rosemary, into a Provencal lamb roast, or melted into oil that is to dress mustardy bitter greens, or hidden in slow-cooked onions, lending depth to a simple pasta sauce, the effect is always the same. By some alchemy, the aged fish lose what can only be called their fishiness – which, you’ll remember from when you opened the tin, was extremely developed – leaving only a profound savour which enhances the taste of almost all animals and animal products (apart from cheese, anchovies go extremely well with eggs, while the smell of them melting into butter is up there with onions for me), though it does tend to overpower the more delicate flesh of white fish. Having left the seaside long ago, they are not readily welcome back.